Forest fires in India are not just seasonal spectacles of smoke and flame; they are ecological crises with complex causes and wide-ranging consequences. From the Himalayan pine forests to the dry deciduous belts of central India, the country faces a steadily growing fire risk — driven by a cocktail of natural vulnerability, human action, and climate pressure. To understand this fully, we need to look at how forest fires start, where they occur, why they persist, and what India is doing (or failing to do) about them.

Where and When Fires Strike

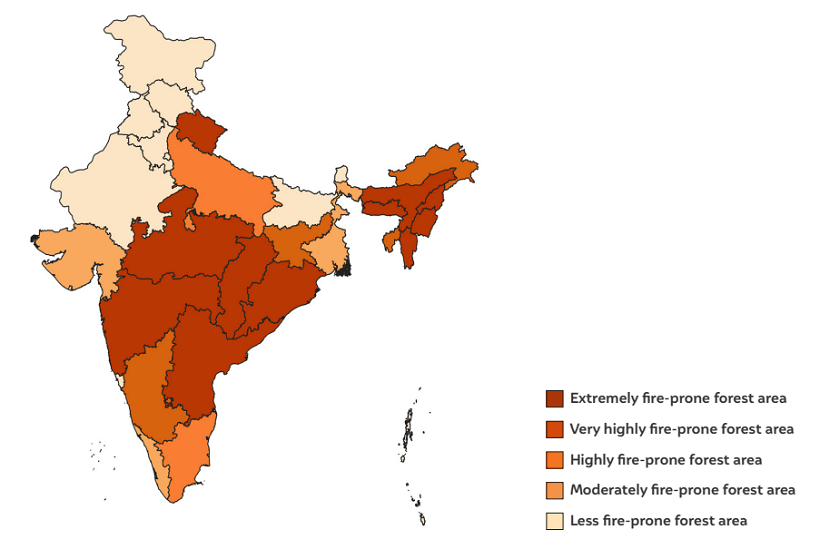

India’s forests span diverse ecological zones — tropical, subtropical, montane, and temperate. But fire is not equally distributed. The most fire-prone states include:

- Madhya Pradesh

- Odisha

- Chhattisgarh

- Maharashtra

- Andhra Pradesh

- Telangana

- Uttarakhand

According to the Forest Survey of India (FSI), over 36% of the country’s forest cover is prone to occasional fires, and around 10% is highly fire-prone. The forest fire season typically runs from February to mid-June, just before the monsoon arrives.

The fires are most frequent in dry deciduous forests, which shed leaves in the dry season. These leaves accumulate into thick, crispy mats — perfect fuel. In places like Uttarakhand, chir pine forests are notorious for burning. Pine needles, loaded with resin, are like nature’s napalm: highly flammable and almost fireproof once lit.

How Fires Start

Most forest fires in India are not natural. Lightning, a common natural trigger elsewhere, is a rare cause here. Instead, fires are mostly human-made, either accidentally or deliberately. Here’s how:

- Traditional Farming Practices: In many tribal and rural regions, locals use slash-and-burn agriculture or shifting cultivation (jhum) to clear land. Fire is a fast tool.

- Grazing and Regeneration: Pastoralists sometimes set fire to old, dry grass to promote fresh growth for grazing.

- Sabotage and Negligence: Some fires are started to conceal illegal logging, poaching, or encroachments. Others result from carelessness — a lit cigarette, an untended campfire.

- Economic Incentives: In chir pine forests, locals collect pine needles (called “pirul”) for biomass briquettes. Fires may be lit to aid collection or claim insurance on degraded land.

The Ecological Fallout

A forest fire is more than just burning trees. It disturbs a whole web of life:

- Loss of Biodiversity: Fires kill ground vegetation, insects, amphibians, and nesting birds. Repeated fires can shift entire ecosystems toward fire-tolerant but biodiversity-poor species.

- Soil Sterilization: Intense fires degrade soil quality, destroy microbes, reduce organic matter, and trigger erosion — especially on hill slopes.

- Carbon Emissions: Fires release vast amounts of carbon dioxide, black carbon, and other greenhouse gases, contributing to both global warming and local air pollution.

- Water Cycle Disruption: Tree loss reduces transpiration, rain capture, and slows the recharge of groundwater. Burned forests dry out the landscape.

And of course, there’s the human cost, especially in regions dependent on forests for food, fodder, fuelwood, and livelihoods.

The Climate Link

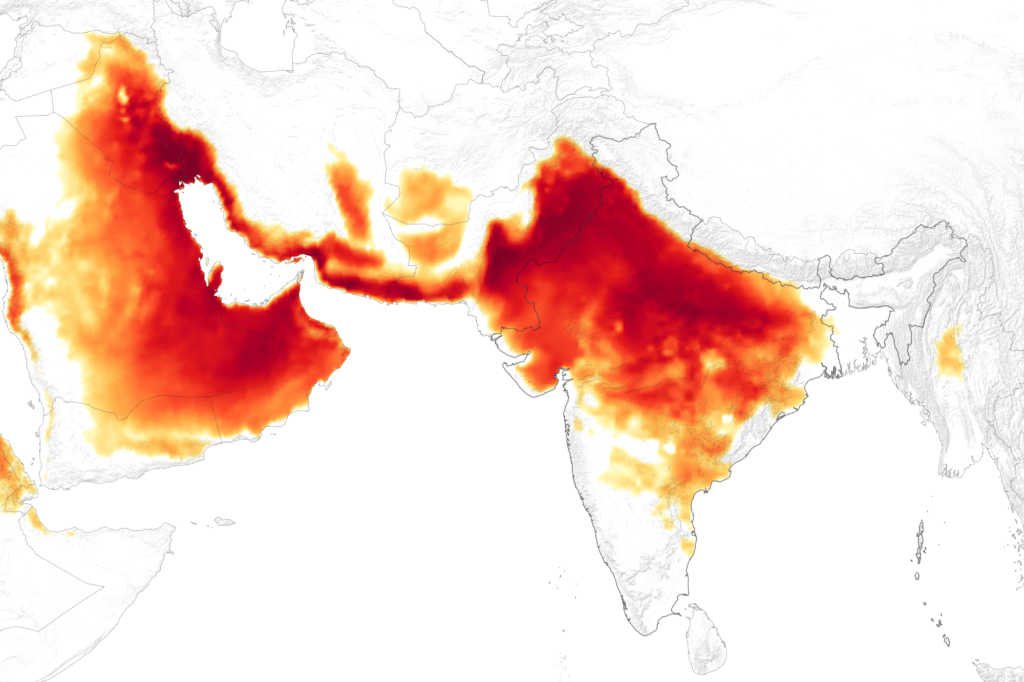

Climate change is not a distant backdrop — it’s an accelerant. India is warming faster than the global average. Rising temperatures and erratic rainfall dry out forests sooner, intensify droughts, and extend fire seasons.

In the Western Himalayas and central India, increased pre-monsoon heatwaves have made forests tinder-dry by April. Even evergreen forests in the Western Ghats — once resistant to fires — are showing vulnerability. Climate change is making the improbable probable.

Detection, Response, and Policy

India has a decent system for detecting fires — on paper. The Forest Survey of India uses real-time satellite data from NASA and ISRO to monitor hotspots via the Forest Fire Alert System (FIRMS). Alerts are sent to forest officials via SMS and email.

But detection is only one part of the puzzle. On the ground, fire response suffers from:

- Manpower Shortages: India’s forest departments are understaffed. Firelines are often not maintained.

- Lack of Equipment: Firefighters in India often rely on beaters and buckets. Helicopters and fire-retardant chemicals are rarely used due to cost.

- Budget Gaps: The National Action Plan on Forest Fires exists but is underfunded. State-level implementation varies wildly in effectiveness.

- Data Gaps: Many smaller fires go unrecorded. Forest loss is often underestimated in official reports.

Indigenous Knowledge and Community Role

One overlooked ally in fire management? Forest-dependent communities. These are not passive victims — they have generations of knowledge about fire behavior, vegetation cycles, and mitigation strategies.

Some NGOs and state programs are now experimenting with community-based fire management, incentivizing locals to create fire breaks, report early fires, and participate in control burns.

The key is shifting from a punitive approach (blaming communities) to a participatory one. If the people closest to the forest are empowered, the forests stand a better chance.

Toward a Fire-Resilient Future

We need to rethink fire, not just as a problem but as a system — ecological, social, and climatic. Fire is not always bad. In some ecosystems, it’s even natural and necessary. But the pattern in India — frequent, intense, and expanding — signals danger.

Some forward-looking strategies might include:

- Controlled Burning: Used in many countries, this means setting small, intentional fires during safe conditions to reduce fuel loads.

- Pine Needle Economy: Turn pirul into a resource — for making paper, packaging, bio-bricks — giving locals a reason to clean forests proactively.

- Fire-Resistant Planting: Reforestation efforts should avoid monocultures and include fire-resistant native species.

- AI and Predictive Analytics: Machine learning models can forecast high-risk zones by analyzing weather, vegetation, and fire history.

- Education and Behavioral Nudges: Outreach campaigns, fire drills, and village-level training can change how people relate to fire.

India’s forest fire story is not just about charred trees — it’s about governance, livelihoods, ecology, and the changing climate. Fires are no longer random blips; they’re becoming part of an emerging pattern of instability. If India is to meet its climate goals, protect biodiversity, and secure its forests, it will have to get serious about fire — not just fighting it, but learning to live wisely in its shadow.

The fire is at the door. Whether we smother it or stoke it further is up to us.